.

FOREVER SUMMERTIME

June 26, 2018 •

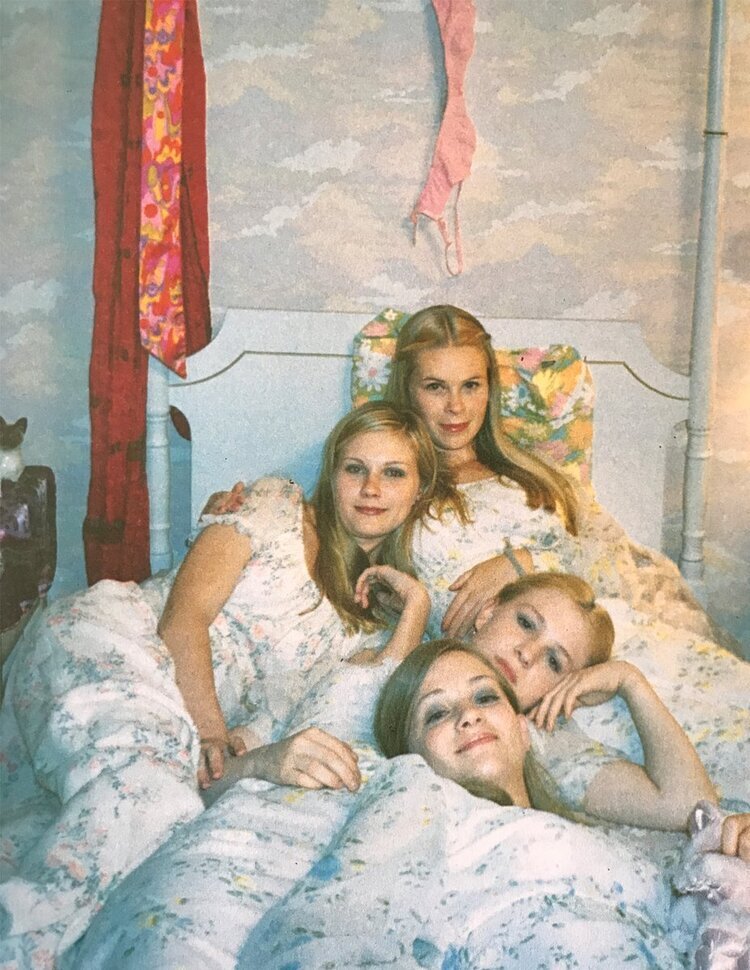

Sofia Coppola’s ‘The Virgin Suicides’: essay by Lorna Irvine.

All of my favourite films have an elusive quality to them: so it is with Sofia Coppola’s debut feature from 1999, ‘The Virgin Suicides.’ It deftly captures the nature of ephemeral youth. Air’s gorgeous electronic soundtrack is elegiac, with throbbing synths emulating blood draining, and the life force ebbing out.

Adapted from Jeffrey Eugenides’ beautiful novel, Coppola retains the lyricism, awkward banality of teenage exchanges and Catholic imagery. It’s like an update of Peter Weir’s 1975 missing girls classic Picnic At Hanging Rock. Terrible things transpire in sunlit corners, away from teacher or parental supervision. Fantasy sequences look like Sara Moon pictures, all languid and ethereal.

Everyone is watching and judging the five lissom Lisbon sisters. Curtains twitch, and ill-judged opinions are proffered from neighbours, as the family’s decline becomes apparent.

Cecilia, the youngest at thirteen, is a key aspect of understanding the family’s dysfunction. Hanna R Hall invests her with a dreamy intelligence, like a suburban Ophelia. When the doctor, played by Danny De Vito, says, ‘ You’re not old enough to know how bad life gets’, she quietly shoots back with a wry smile, ‘Obviously Doctor, you’ve never been a thirteen year old girl’. Her first suicide attempt is heartbreakingly prettified by Mom (a brilliant Kathleen Turner) putting bracelets over her bandages. Just kid on it never happened, and the problem will go away. Sheer denial.

Mrs Lisbon is mostly the problem here, as well as her timid husband, the maths teacher played by James Woods, denying the teens’ burgeoning sexuality: obsessive Catholics micromanaging every single aspect of the girls’ lives, from not dating to not even expressing inner thoughts in diaries. Would Therese (Leslie Hayman) be so shy at seventeen if she wasn’t so oppressed? Of course not, she’d most likely be more independent.

The girls, despite being intelligent and articulate, are far from perfect. They cling together like limpets, haughtily making sardonic asides. One horrible scene sees them laughing at a disabled kid, Joe. Only sensitive Cecilia treats him with dignity. It’s a sour moment of bowing to peer pressure, and leaves a bitter taste. Cecilia is pushed over the edge.

It is local boys, as adults, who narrate the film, still creepily obsessed with them: the male gaze is a vital component here, as it serves to show how mysterious and complex girls are to boys growing up. Only in retrospect, do they see: ‘ They were really women in disguise.They understood love, and even death. Our job was to create the noise that seemed to fascinate them’.

Only one boy can penetrate (steady!) the Lisbon family- the stoner kid Trip Fontaine (Josh Hartnett). Trip is a swaggering tart, a Travolta- alike with floppy hair who exploits his looks at every available opportunity. He seduces the willing, rebellious Lux (Kirsten Dunst) after persuading the parents to take the girls to Homecoming Dance. Of course, he then abandons her on the football pitch where he took her virginty, thus reinforcing the ‘danger’ of male heterosexuality.

This sets about the beginning of the end, as the girls are taken out of school and their FILTHY rock records burned and binned. This scene is almost a foreshadowing of the moral panic in 80s America, as Tipper Gore railed against lewd lyrics and founded the ultra- conservative PMRC.

It’s deeply symbolic that the Lisbon residence is never shown in winter, only summer-autumn. This mimics the curtailing of young lives – forever sealed in a summer haze. “They fuck you up, your mum and dad”, as Philip Larkin once observed. A beautiful, unforgettably poignant film.

First published in The Tempo House,2018.

..

..

.